Indie Edge April 2011: Dean Mullaney

Mar 18, 2011

|

|

Dean Mullaney (who launched Eclipse Comics in 1977 with his brother Jan) has been one of the driving forces in the independent comics field, blazing trails in the early publication of original graphic novels as well as being one of the early publishers of Japanese manga (with Viz). Eclipse also brought us a minor superhero named Miracleman… but that’s another story.

These days, Dean Mullaney can be found working with IDW Publishing, overseeing his impressive “Library of American Comics” archival series, which includes classics like Blondie and Terry and the Pirates to more modern fare, like Bloom County.

In honor of our month-long tribute to cartoons and comic strips, Dean took time out of his busy schedule to discuss his process, his favorite projects, and much more!

PREVIEWS (P): Hello Dean, would you please tell us a little bit about your work with IDW and the Library of American Comics line?

PREVIEWS (P): Hello Dean, would you please tell us a little bit about your work with IDW and the Library of American Comics line?

Dean Mullaney (DM): I created the Library of American Comics in 2007 with the goal of preserving the best of the classic newspapers in definitive archival editions and framing them with informative essays that place the series in historical context, both in relation to other strips and to the current events of their time. My love for and interest in classic newspaper strips goes back more than forty years.

(P):What has been your favorite project, and what drew you to the artist or the characters?

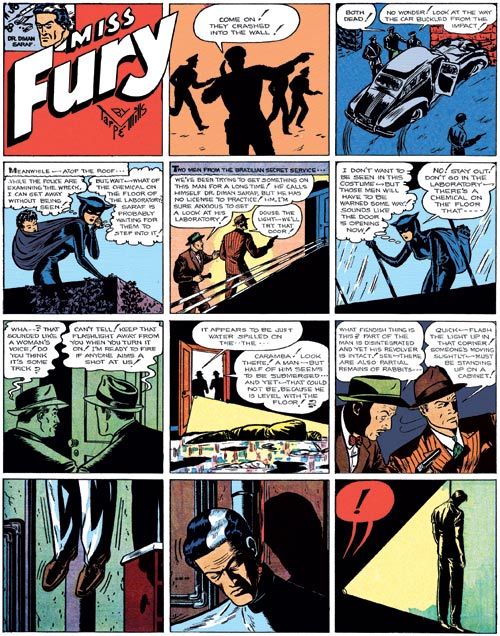

(DM): That’s a difficult question to answer because there are several “favorites”: “Genius, Isolated: The Life and Art of Alex Toth” that’s just been published is very close to my heart because I knew Alex and worked with him; it’s been a great pleasure to produce this book in conjunction with Alex’s family. Two other favorites are “Scorchy Smith and the Art of Noel Sickles” and “Polly and Her Pals” because both Sickles and Cliff Sterrett were unique, singular talents who created styles like no other. But if I had to pick one strip, my favorite remains Milton Caniff’s “Terry and the Pirates,” which, in my opinion, is simply the best written and drawn adventure strip ever done.

(P): What was your role in getting your favorite project ready for eager readers? How many staff members do you tend to have on your team?

(DM): I am the imprint’s Creative Director, which means I decide which books are produced. I also edit and design most of them, but the success of our line is also due to the heroic efforts of Bruce Canwell—who’s the associate editor of every book and who writes what have been called the best historical essays about comic strips, and Lorraine Turner, our associate art director and designer who also oversees much of the Sunday page color restoration. Scott Dunbier, one of IDW’s senior editors, edits several titles; and IDW’s publisher Ted Adams happily keeps the whole ball of wax rolling. We also use freelance writers and researchers, and about a half a dozen production assistants who, for the most part, make the daily strips ready for publication.

(P): Many daily strips’ original art was sold, destroyed or lost. What sources were available when you were collecting art for your favorite project?

(P): Many daily strips’ original art was sold, destroyed or lost. What sources were available when you were collecting art for your favorite project?

(DM): Sources vary. Under ideal circumstances, we locate the original art, such as with Harold Gray’s archive of “Little Orphan Annie” strips at Boston University.

In other cases, as in “X-9: Secret Agent Corrigan,” we’ve been granted access to the artist’s syndicate proofs.

For the most part we use tearsheets, the printed strips as they appeared in newspapers. For “Terry and the Pirates,” we used a combination of syndicate proofs and tearsheets from the phenomenal archive at The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Art Library and Museum.

(P): Depending on art sources, the original image quality may have been greatly degraded. How does your production team go about retouching the art?

(DM): We spend countless hours in Photoshop, sometimes as much as 4-6 hours per Sunday page. Doing proper restoration takes more than just knowledge of Photoshop’s tools—it takes a full understanding of the strip and the artist’s style, as well as a commanding knowledge of the four-color printing process from decades past. Some publisher’s take the artifact route—that is, presenting yellowed and discolored pages “as found.” At the Library of American Comics our motto is “art, not artifacts.” Artists such as Milton Caniff spent a great deal of time preparing color guides for their Sundays, and I think part of our job is to restore those pages to what the artist originally intended.

(DM): We spend countless hours in Photoshop, sometimes as much as 4-6 hours per Sunday page. Doing proper restoration takes more than just knowledge of Photoshop’s tools—it takes a full understanding of the strip and the artist’s style, as well as a commanding knowledge of the four-color printing process from decades past. Some publisher’s take the artifact route—that is, presenting yellowed and discolored pages “as found.” At the Library of American Comics our motto is “art, not artifacts.” Artists such as Milton Caniff spent a great deal of time preparing color guides for their Sundays, and I think part of our job is to restore those pages to what the artist originally intended.

(P): How long does a project generally take you, from the green light until it goes to press? What takes the longest? Have there been any unexpected roadblocks as you pull together older material?

(DM): This varies from book to book, depending on the availability of source and research material. What takes the most time is the tedious and exacting job of restoring the strips to their original condition. The biggest roadblock is usually locating the best quality strips from which to work.

(P): How does IDW/Library of American Comics select titles for this kind of treatment?

(DM): In 2007, Bruce Canwell and I created a long “to do” list, and we’re working out way through them one by one. Our goal is to not merely present classic and important strips, but to offer a well-rounded library of various styles and genres. The Library’s line-up ranges from the whimsical “King Aroo” to the blunt and violent “Dick Tracy” to the deliciously illustrative “Flash Gordon.”

|

(P): What upcoming titles are in the works for your editorial team?

(DM): Later this year, the ultimate “Flash Gordon” with the “Jungle Jim” topper is probably the most exciting new series. We’re producing it in our Champagne edition size: 12” x 16”, just like “Polly and Her Pals,” which one reviewer called “the most gorgeous book I’ve ever seen.” We’re also working on an unknown gem: a short-lived newspaper strip by the legendary Chuck Jones. Entitled “Crawford,” it only ran for six months in the 1970s. The Academy Award-winning director of some of the greatest Warner Brothers cartoons first created the character for a never-produced TV special. From the Chuck Jones estate’s files, we’re reproducing almost all of the strips from the original art, as well as the never-before seen storyboards, unused gags, and preliminaries. It’s an amazing Chuck Jones art book that no one—even the most diehard animation fans—knew existed!

(P): What has the reception been like in the book market for these collections? Are you finding a significant audience there? Do you have a sense for the demographics of your readership?

(DM): The reception has been fantastic, both in the book market and among comics fans. We’ve been called “the gold standard for archival comic strip reprints,” while others have noted that “no publisher is more dedicated to archival collections.” In our first three years, we’ve been nominated for ten awards and have walked home with two Eisners.

The question of demographics is interesting. No one has any hard facts—we can only go by mail and feedback from readers. It appears that our readers fall into one of three general categories: Long-time newspaper strip fans who have been waiting many years for this “Golden Age” of comic strip reprints; professional comic book creators and up and coming artists who want to study the works of past masters; and comic BOOK fans who are bored with current comics and are just now beginning to explore the great comic STRIP creators.

(P): For a lot of readers, these collections might be their first exposure to these classic strips (for example, Miss Fury). What is it about these strips that you think still holds appeal for readers today?

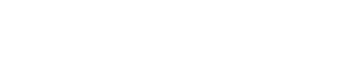

(DM): Although art styles change over the years and may fall in and out of favor, superior storytelling and compelling narratives are timeless. Tarpé Mills, who wrote and illustrated “Miss Fury,” is a prime example. In 2011, one could call her 1940s art “old school” or you could call it “classic.” It depends on your outlook. Her strip—the first costumed female superhero created by a woman—is definitely a strip of its time. It’s a bang-up adventure story that’s also full of human interest, gorgeous women, and handsome, exotic men.

|

(P): Some of these strips have been celebrated since their release and others are more “products of their time.” Do you feel that the Library of American Comics may help bring about a renaissance for these titles? How important is it that readers be reminded of the social context of the times when the strips were created?

From the Library’s inception, it’s been our goal to bring about a renaissance for classic newspaper comics, and I think it fair to say that we’ve succeeded. In a recent review of “Polly and Her Pals” in Booklist, Gordon Flagg wrote, "The early years of newspaper comics produced a handful of widely acknowledged masterworks, such as Little Nemo and Krazy Kat; this impressive collection makes a convincing case that Sterrett's creation should be added to that honor roll." This is precisely why we’re spending so much time researching and restoring these strips. Hardcore strip fans have long believed that Cliff Sterrett is, with George Herriman, one of the handful of masters of the form. In reprising Sterrett’s masterpiece in a new edition, everyone can now enjoy and appreciate his brilliance.

(DM): Placing the strips in historical context—both in relation to other strips and to their time—is one of our most important tasks. To paraphrase E. B. White, it’s our job as writers and editors to lead the reader through the swamp and offer clarity and insight to the material. For example, strips prior to the Second World War sometimes contain racial and ethnic stereotypes, or politically-incorrect portrayals. Our mission is to preserve these strips as published, yet to provide context and explanation.

|

(P): A lot of these strips got their starts in newspapers. With the size and number of newspapers in the U.S. shrinking, do you think this will impact the art of storytelling in a “panel strip” format? Do you feel that ‘webcomic strips’ will fill the void of declining newspaper circulation? Without an editorial body overseeing their production, do you feel that webcomics match the quality of the storytelling found in many of the newspaper serials?

(DM): No one knows how long newspaper strips will continue to exist. In fact, we don’t know for how many years newspapers themselves will exist in their current format. It’s clear that the trend is for information to move online. Webcomics are a great addition to the medium, but I don’t see them as a replacement for printed strips. Most webcomics are the equivalents of daily strips; I’d like to see more cartoonists look back to the classic half page Sunday strip—the proportions of half-page Little Orphan Annie and Dick Tracy Sundays are ideal for the size of a computer monitor, or an iPad turned horizontally.

Whenever new technologies have been invented, the new kid on the block borrows or adapts from previous ones. For example, most early television shows were simply radio shows translated to the screen. Current webcartoonists would do well to study the past, but not be enslaved by it. There’s no reason to ignore the past, and every reason to learn from it.

(P): Thank you again for all your hard work preserving American literature, humor, and history.

**********

The American Lirbary Of Comics

Available Now!

|

THE COMPLETE LITTLE ORPHAN ANNIE HCs

POLLY & HER PALS VOLUME 1: SCORCHY SMITH AND THE ART OF NOEL SICKLES HC (APR083922) |

THE COMPLETE TERRY & THE PIRATES HCs |